Vikings and Gall-Ghàidheil in Galloway

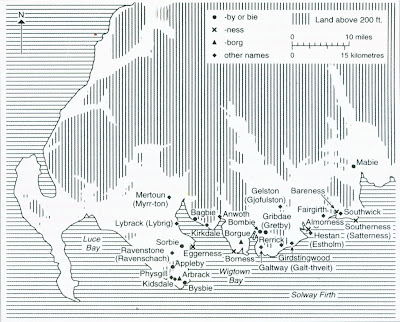

Evidence for Viking settlement in Galloway is limited to two clusters of Norse settlement names in the Machars and the coastal fringe of the Stewartry as the map below illustrates.

As the first map shows, these were already well settled locations, corresponding to better quality (suitable for arable crops) land- as this land use map shows. It is from 1944 and shows arable land brown, good pasture pale green and rough/ poor grazing land yellow.

The Vikings who settled in these areas were probably from Dublin originally and likely to have been traders rather than farmers. They settled in the good quality land areas because that is where most of the people lived and because these areas were close to the sea and its trade routes.

However, by the time Timothy Pont surveyed Galloway circa 1590, settlements (farms) were far more widely distributed. I have 'dotted' in the farms and settlements shown on Pont's map of Galloway

Although Gaelic was extinct in Galloway by Pont's time, most of the farms he shows had Gaelic names which means that the people who extended the settlement pattern in Galloway into the Moors of Wigtownshire and the hills of the Stewartry were Gaelic speakers. Where did they come from? There is likely to have been some settlement by Irish Gaelic speakers, especially in the Rhinns, but again, as this map shows, it was along the coastal fringe.

This suggests that the main movement of Gaelic speakers into Galloway had another source. The most likley candidates were the Gall-Ghaidheil. The Gall-Ghaidheil are most likely to have originated in the Argyll/ Kintyre area when a group of Vikings were absorbed into a Gaelic speaking community and became Gaelic Vikings (Gall being the Irish/ Gaelic word for Viking at this time- ninth century).

The Gall-Ghaidheil expanded their influence around the Firth of Clyde into Renfrewshire and Ayrshire, before moving south into Galloway by land. The Gaelic speaking area occupied by the Gall-Ghaidheil formed a 'Greater Galloway' by the eleventh century.

David Parsons [Journal of Scottish Name Studies Vol. 5 2011] has suggested they may also have crossed the Solway to settle in north-west England. However, during the twelfth century, 'Greater' Galloway began to contract to the boundaries of present day Galloway and the kingdom established by Fergus of Galloway. In this 'lesser' Galloway (which included Carrick in Ayrshire), Gaelic survived into the fifteenth century. Most of the farms forfeit by the ninth earl of Douglas (as lord of Galloway) in 1455 had Gaelic names.[The map misses out two significant clusters of Gaelic named farms in the north of Kirkcowan and Penningham parishes.]

It is possible that some of the lands forfeit by the ninth earl of Douglas had been part of the pre-Douglas lordship/ kingdom of Galloway. If so, then the inclusion of farms in the uplands of Galloway is significant, since they give a potential link to the period of Gall-Ghaidheil settlement in the tenth and eleventh centuries.

My suggestion is that prior to the Gall-Ghaidheil influx, the settlement patterns in Galloway were still those shown on the first map, concentrated in the better quality lowland farming areas. If the Gall-Ghaidheil practiced a different style of farming, a style perhaps of cattle farming, which was able to take advantage of poorer quality land, they could then have opened up large areas of Galloway to settlement.

In the other areas where the Gall-Ghaidheil settled (other parts of south-west Scotland and in north-west England), existing settlements were more intensive/ extensive, so their long term impact ( Gaelic language) was less marked, but in Galloway they were able to become the dominant linguistic and political group.

The end result was the creation of an integrated farming economy in Galloway, supporting both arable and livestock farming. By introducing Cistercian monks and improved 'Norman' style arable farming, Fergus and the later lords of Galloway actively balanced cattle farming with other types of farming. This pattern of mixed land use survived into the eighteenth century.