When the levee breaks..

"When The Levee Breaks" Led Zeppelin 1971

If it keeps on raining, levee's going to break,

If it keeps on raining, levee's going to break,

When the levee Breaks I'll have no place to stay.

Mean old levee taught me to weep and moan

Mean old levee taught me to weep and moan

It’s got what it takes to make a mountain man leave his home,

Oh, well, oh, well, oh, well.

Don't it make you feel bad

When you're tryin' to find your way home,

You don't know which way to go?

Cryin' won't help you, prayin' won't do you no good,

Now, cryin' won't help you, prayin' won't do you no good,

When the levee breaks, mama, you got to move.

The original lyrics to this song were written by Memphis Minnie in 1927. Memphis Minnie McCoy (born Lizzie Douglas), was a Blues artist who recorded this in 1929. Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin had the record in his collection. The lyrics are based on The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. African-American plantation workers were forced to work on the levee at gunpoint, piling sandbags to save the neighbouring towns. Hence the original lyrics, "I works on the levee, mama both night and day, I works so hard, to keep the water away." After the levee breached, blacks were not allowed to leave the area, and were forced to work in the relief and cleanup effort, living in camps with limited access to the supplies which were coming in. Many left at the first chance since there was no work in the Delta after the destruction of all of the plantations; hence the original lyrics, "Oh cryin' won't help you, prayin' won't do no good" and "It's a mean old levee, cause me to weep and moan, gonna leave my baby, and my happy home" [From website

http://www.songfacts.com/detail.php?id=335 ]

But what has any of this got to do with Dumfries and Galloway? Well, apart from the fact that Led Zeppelin were very much part of popular music/ youth culture when I was a teenager here, the theme ‘if it keeps on rainin’, levee’s goin’ to break’ has strong current significance. The past month has seen ‘exceptional’ rainfall. This has resulted not just in the usual flooding of Dumfries town centre, but the breaking of a ‘levee’ / flood defence built by French (Napoleonic) prisoners of war around 1800 beside the river Ken. This gives a ’people and place’ link to the Mississippi levees since they were first built by French settlers around New Orleans in the late 18th century.

And if it keeps on raining - which is a predicted outcome of the local impact of global warming/ climate change- what then? The local ‘levees’ the French prisoners-of-war built 200 years ago were subsequently extended as part of the Galloway Hydro-Electric Power Scheme, completed in 1936. The whole course of the Deugh/ Ken/Dee river system (plus the river Doon system) was affected by this economic development via a series of dams, tunnels, barrages, aqueducts and pumping stations. Although the current flood warning status (15 December 2006) is ‘All Clear’, the height of water behind the dams on the Hydro-electric system is still a at maximum.

The Galloway Hydro Electric Power Scheme was planned and designed in the 1920s. Historical studies of maximum flood-levels were carried out (example from memory: a stone marking the highest 19th century flood-level near Crossmichael village was surveyed). But if we are now entering a period of increased rainfall, will this ageing system be able to cope? The Napoleonic levees’ on the Ken have been breached for the first time in 200 years. Could one of our 70 year old concrete dams also fail?

Probably not, but if keeps on raining their floodgates will have to be kept open, thus raising water levels throughout the whole river system. This in turn will put extra pressure on the riverside ‘levees’ and these could (as one already has) break.

If it keeps on raining… the re-emergence of history.

Even without a levee break, as the rain keeps on falling an almost forgotten past is re-emerging.

In the area around Castle Douglas, a 5km long strip of marshland stretches from the river Dee at Threave castle island down to Gelston village. Carlingwark loch lies at the centre of this area, most of which is now under water. Only a small section of higher ground near Gelston separates the flooded area from the Doach Burn which flows down to the sea at Orchardton Bay. During the last period of ‘ global warming’, at the end of the last Ice Age about 15 000 years ago, water from melting glaciers carried the river Dee along this direct route to the sea. Only after all the ice had melted and drier conditions prevailed did the river adopt its present route to the sea at Kirkcudbright, changing its course at Threave castle island.

The drier and warmer period lasted up until about 3000 years ago, when colder and wetter conditions returned. It has been speculated that this climate change had an impact on local culture, farming and settlement patterns. One consequence may have been the placing of votive offerings in rivers, pools, springs, bogs and lochs. These in turn may have been attempts to ritually/ symbolically/ practically ’manage’ the consequences of this climate change. Unfortunately, we cannot ask the people who did this why they acted so. All we know is that they did and that over the past 200 years or so, the items they placed in rivers, springs, pools, bogs and lochs have been recovered, described by archaeologists and placed in museums.

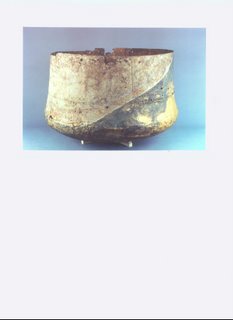

Several such objects have been found in the area around Castle Douglas. These include a ‘pony cap’ plus parts of two drinking horns found around 1826 in a bog (previously a loch) on Torrs farm and a large bronze cauldron found in Carlingwark Loch in 1868. Of these, the cauldron contained over 100 smaller metal items. Since these included a few pieces of Roman metal work, including a piece of Roman chain mail, the cauldron must have been placed in the loch after the Romans came to Britain (unless the Roman items reached Carlingwark Loch through trade before then) and most likely after the Romans reached Galloway, which the did around 80AD. The Torrs Pony Cap and drinking horns appear to be earlier, with an estimated date of manufacture (from stylistic features, possibly in eastern England) of around 250 BC.

Can any more be said? From the evidence of the objects alone, not much. There is no way to tell when they were ‘placed in context’ since both were found accidentally and long before archaeological practices which could have provided such information existed. Had either of the objects been found more recently, their discovery would have triggered detailed on-site ‘forensic’ archaeological investigation. The fact that the Carlingwark Cauldron was found [Harper : Rambles in Galloway: 1876] close to Fir Island would surely also have prompted an investigation of the ‘Ash Island’ crannog site, since it is connected by an underwater causeway to Fir Island. [From survey carried out by Keith Kirk, D and G Council Countryside Ranger in 1995].

Amongst the Roman metal work items found inside the Carlingwark Cauldron were scythe blade fragments. In the National Museum of Scotland (where the Carlingwark Cauldron is on display) can be found a set of complete Roman scythe blades. The NMS explain that such scythes were introduced by the Romans and used for cutting hay as fodder for cavalry units. Two miles north of Carlingwark Loch, the Romans built a series of two (possibly three) forts and six marching camps. These lie beside the river Dee in an area of high quality farm land, one of the few places locally where wheat can be grown (from personal observation and adjacent place name ’Wheatcroft’ ).

Although the area of high quality farm land on which cereal crops like wheat can be grown borders the river, in the Roman period and until the ’levees’ were built, a practical problem prevented this. The practical problem was three fold. Firstly, ields closest to the river would be too wet to be ploughed in winter, secondly they would still too wet to be planted in the spring and thirdly the Ken/Dee river system had a habit of flooding at harvest time (August/Lammas). The practical solution arrived at was to crop hay from riverside fields. Even then, as local author S.R. Crockett [1859- 1914] who was brought up on Little Duchrae farm beside the Dee recalled, as a child he had to rush out in the middle of the night to save the family’s hay-crop from the river‘s Lammas floods. The hay was sold to pay the rent on the farm. Hay was an essential crop - it was needed to feed livestock during the winter.

Crockett also mentions the Dee flooding back up into Carlingwark loch. This makes me wonder if, 1800 or so years before, there was a perceived connection between loch and river? The river’s name - Dee- comes from Dea or Deva meaning ’goddess’. The Dee/ Ken system is navigable for 15 miles upstream from Threave castle island. A place name Locatrebe/ Locatreve is recorded in the 7th century Ravenna Cosmography. Andrew Breeze (Transactions DGNHAS: 2001: 152/153)

translates this as corresponding to the Welsh llwch ‘lake, pool, stagnant water, bog, swamp, marsh; mud mire, grime filth’ plus Welsh tref ‘ homestead, settlement ;home, town’. Breeze mentions the Carlingwark Cauldron and Torrs Pony Cap in his discussion of possible locations for Locatrebe, suggesting it may refer to the Roman forts and marching camps complex at Glenlochar rather than Threave castle island (as suggested by Editors of Transactions).

However, there was also an Iron Age ring fort on Meikle Wood Hill, midway between Carlingwark Loch and Threave castle island and which overlooks both river and Carlingwark marshes. Allan Wilson (The Novantae and Romanization in Galloway: Transactions DGNHAS: 2001:81) suggests the area was a centre of power, which the Glenlochar complex would have controlled. Wilson also mentions ‘the bronze head of a Roman war-horse’ found (but now lost) near Glenlochar. Could this have been a Roman chamfron (protective armour for a cavalry horse’s head)? If so, it would give a link to the similar Torrs’ Pony Cap.

It is all a bit speculative and frustrating in the absence of archaeological investigation of the sites. My speculation is that there was an important centre of ‘power and wealth’ here 2000 plus years ago and that this included a centre of ritual/religious importance focused on the immediate area around Carlingwark Loch. The Dee/Ken river system would have been important in the development of this centre by acting as a transport route. Whoever controlled the river system could draw on ‘tributes’ from everyone living along it. Sacks of grain (for example) could be put on boats upstream and floated down to ‘Loctreve’ far more easily than they could have been carried on horseback overland to alternative centres.

Even when overland trade routes are taken in to account, ‘Locatreve’ lay at a crossroads between east/west and north /south routes. The east/west route along a series of ridges of higher ground (as later followed by the Old Military Road between Gretna and Portpatrick/ Stranraer, England and Ireland and today’s A 75 Euro-route) passes through the Locatreve / Castle Douglas area. A north/south route from Ayrshire and the Firth of Clyde to the Solway Firth crosses the east/west route here as well. Perhaps significantly, unlike the Annandale ‘transport corridor’ up and down which armies marched from Roman to Jacobite times, these local routes have rarely been of national rather than local historical significance. Thus their importance and that of Locatreve exists as part of local rather than national history.

And yet… the very presence of the Carlingwark Cauldron and Torrs Pony Cap as part of the National Museum of Scotland’s collection implies that this ‘local‘ has ‘national’ importance. But if local has national importance, why has there been no national level archaeological investigation of their context?

“Funding” is no doubt one answer. But I suspect another is ‘ideological’. The Torrs Pony Cap and the Carlingwark Cauldron are part of a world , of a reality, which existed before ‘Scotland’. To pursue the reality which such physical artefacts embody is to pursue a reality in which ‘Scotland’ does not exist.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home